The sunlight streaming through the sepia-red corton steel bars of Edra Soto’s GRAFT (2024) installation at Doris C. Freedman Plaza in Central Park decorates the asphalt terrace with geometric patterns of light and shade that bring forth a flickering rush of memories.

Morning sun rising through the window grates of my cousin’s teenage bedroom while someone brews coffee down the hall. The coolness of the damp golden sand shielded by palm frond silhouettes. Fading light sinking down textured terracotta walls in my aunt’s Ocean Park courtyard.

Though the work itself also feels familiar, reminiscent of so many homes and places in my family’s native Puerto Rico, there is something specifically about the way Soto’s art interacts with the space it inhabits that strikes a particularly resonant chord.

Read MoreIn her lecture “On Beginnings,” collected in the book Madness, Rack, and Honey, the poet Mary Ruefle considers Gaston Bachelard’s idea that “we begin in admiration and end by organizing our disappointment,” which she simplifies even further into “origins (beginnings) have consequences (endings).” Pulled and paraphrased from Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, where it originally referred to the practice of poetry and the ways we deal with the intrinsic inadequacies of language, it is a concept that can also be applied to an act even more mystical and bewildering: that of falling in love.

As Ruefle elaborates, “the moment of admiration is the experience of something unfiltered, vital and fresh” not unlike the sense of potential, amazement, and naivete with which one might enter a new romance. As the initial illusions fade and the realities make themselves known, the clarity afforded by disappointment becomes an opportunity to take agency and make decisions in marked contrast with the uncontrolled fall at the onset. Or as Ruefle puts it, a moment of “dignification” where the writer—or for our purposes, the lover—can take back control of the story.

For writer and director Nora Ephron, dignifying the consequences of her origins meant using it as fodder for her literary work. From the Esquire magazine essays that pulled from her daily life to the dynamic romantic comedy heroines she wrote to deliver her personal philosophies on screen like Meg Ryan-shaped ventriloquist puppets, Ephron was an unapologetic miner of her own lived experience; a self-described “cannibal” who took her screenwriter mother’s adage to heart that “everything is copy.”

Read More“There was a time when I would rather have had you by my side than any one of these words; I would rather have had you by my side than all the blue in the world.”

I chose Bluets because I wanted to learn how to let go of a dream.

In the first version of that sentence, I wrote: a dream that no longer fit, but then went back and removed that part because it’s not really that the dream doesn’t fit; it’s simply that I want to wear something else, regardless of how good the dress looks.

(Then again, multiple things can be true because I can also think of all the ifs that would have made me want to keep wearing that dress.)

I try to explain this to my best friend, but he doesn’t understand because so many of the ifs went his way. Our conversation keeps getting interrupted because HBO and Hulu are in a bidding war over one of his films. When he returns to the table I say: it doesn’t make sense to you because the same people who keep offering you more, keep offering me less.

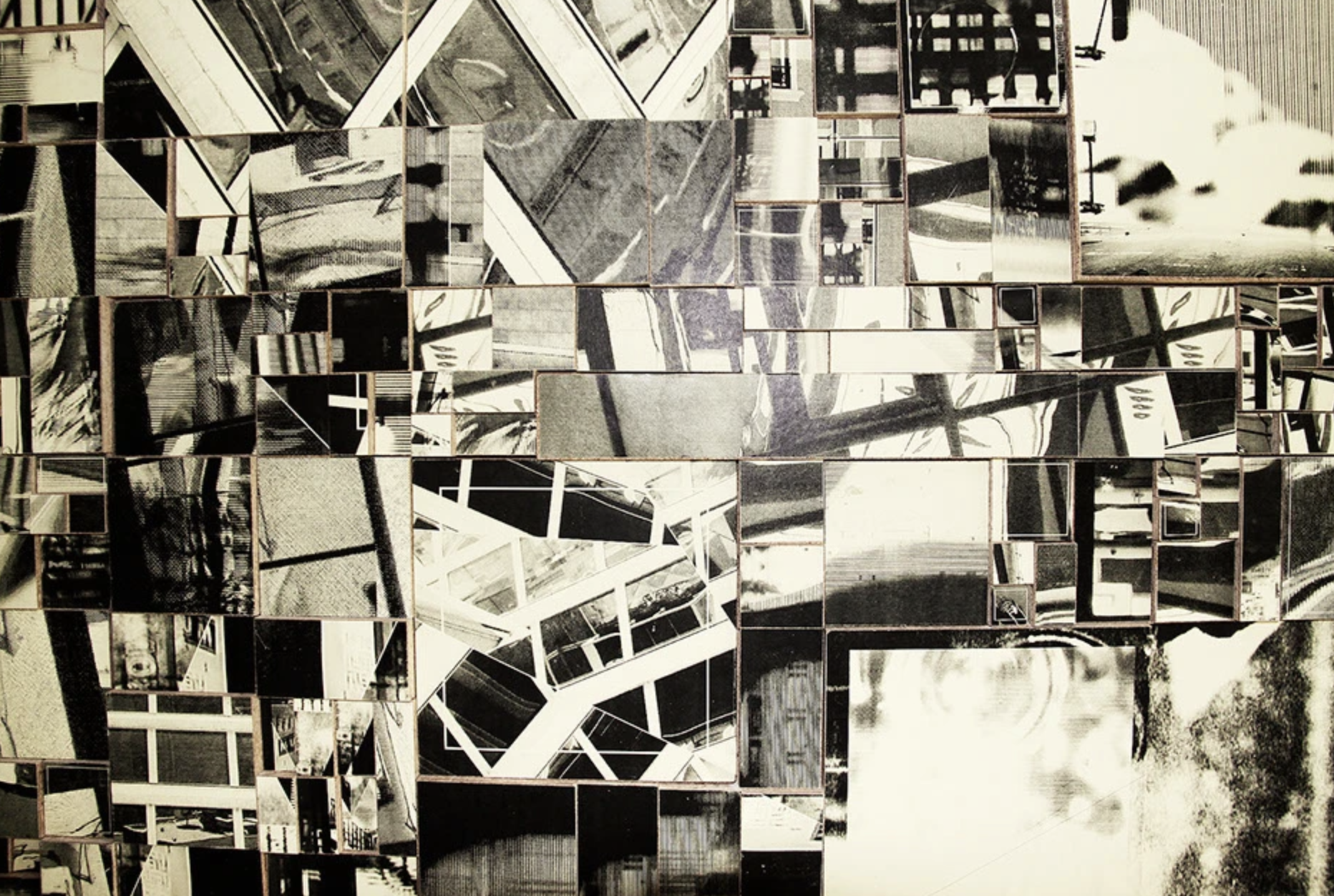

Read MoreStepping into Rem Koolhaas’s legendary essay “Junkspace” is a disorienting experience. Existing in a liminal space somewhere between prose poetry and art manifesto, Koolhaas’s words on the state of modern architecture and building design boldly challenge the reader from the onset. One doesn’t need to read a single word to find its 16 pages of justified text, lack of paragraph breaks, and unconventional punctuation, visually arresting. Moving further into the text reveals the content of the essay echoes the incongruity of the style. From its bizarre opening declaration that “Rabbit is the new beef” through to its concluding ellipsis, we immediately recognize that this is not a traditional essay, but rather one that pushes us past the boundaries of the mainstream to deliver its message.

We begin with the one-word title “Junkspace,” which can be read as either uncharacteristically straightforward or frustratingly deprived of context. That this essay is where Koolhaas first introduced this word, which is entirely of his own making, strongly suggests the latter. Either way, the essay is an exploration of junkspace, a term Koolhaas has coined to refer to current trends in buildings and other designed spaces which he finds have devolved into a state of being somehow both function-driven and form-less, where commerce, artifice and expansion dominate all other motives.

The term is a play on the concept of “space-junk,” defined as the debris humans leave behind while exploring space. To Koolhaas, the inverse junkspace “is the residue mankind leaves on the planet”. It is the “fallout” that remains after the program of “modernization has run its course”. Koolhaas seems to lament that despite existing in a time when we are building more and have more freedom than ever before, “we do not register on the same scales. We do not leave pyramids”. We only leave junkspace. In other words, junkspace is the disappointing denoument of humanity’s progress.

Read MoreI’m endlessly seeking shortcuts. In an effort to buy back precious minutes lost to reasons both cognitive and cultural, I’ve gamified my commutes, perpetually scanning my environment for more efficient ways to get where I need to go. With the precision of a skilled hunter, I skip entire city blocks by cutting through semi-public buildings, calculate the risks of jay walking across thoroughfares, and shamelessly trample diagonally across beautifully manicured, but inconveniently placed lawns. Sidewalks become mere suggestions. “Keep off the lawn” signs? Challenges. My need to get where I need to go as expeditiously as possible always superseding the plans set for me by some distant figure. As creative as these choices may feel, these meanderings are not unique to me, but rather part of a centuries long tradition of living beings charting alternate paths.

They’re called desire paths, an undeniably romantic name conveying sentiments of yearning both illicit and indulgent. At their simplest definition, desire paths—also known as desire lines—are natural unpaved pathways created by human inclination and instinct, rather than planning. It’s the worn dirt path cutting through a grassy college quad. A sandy shortcut leading down to the beach. The track of slushy muddy footprints slashing through an otherwise pristine blanket of white after a snowfall.

The visuals can be arresting, poignant, even humorous, serving to convey seemingly universal truths about animals and humans alike. To some, desire paths are found art waiting to be discovered in the most prosaic of places. An exquisite corpse created collaboratively by paws, feet, or bicycle tires motivated through equal parts impatience and curiosity. To others, the trampled lines take on deeper symbolic meaning representing everything from charming ingenuity and independence to civil disobedience, protest, and even anarchy. In every case, desire paths illustrate a fundamental tension between theory and practice, planning and usage, and the myriad ways humans relate to their built and natural environments.

Read More