I try to remember to pack a few black washcloths when I travel for work. I place them next to the hotel sink, ready to be used when I get back from a shoot, sparing the provided pristine towels from smears of jet black mascara and kisses of Dior 999. When I forget, the association is immediate. A face imprinted on cloth. An unintentional self-portrait—not of my own face, but of the one I wear to do my work…

Read MoreThe sunlight streaming through the sepia-red corton steel bars of Edra Soto’s GRAFT (2024) installation at Doris C. Freedman Plaza in Central Park decorates the asphalt terrace with geometric patterns of light and shade that bring forth a flickering rush of memories.

Morning sun rising through the window grates of my cousin’s teenage bedroom while someone brews coffee down the hall. The coolness of the damp golden sand shielded by palm frond silhouettes. Fading light sinking down textured terracotta walls in my aunt’s Ocean Park courtyard.

Though the work itself also feels familiar, reminiscent of so many homes and places in my family’s native Puerto Rico, there is something specifically about the way Soto’s art interacts with the space it inhabits that strikes a particularly resonant chord.

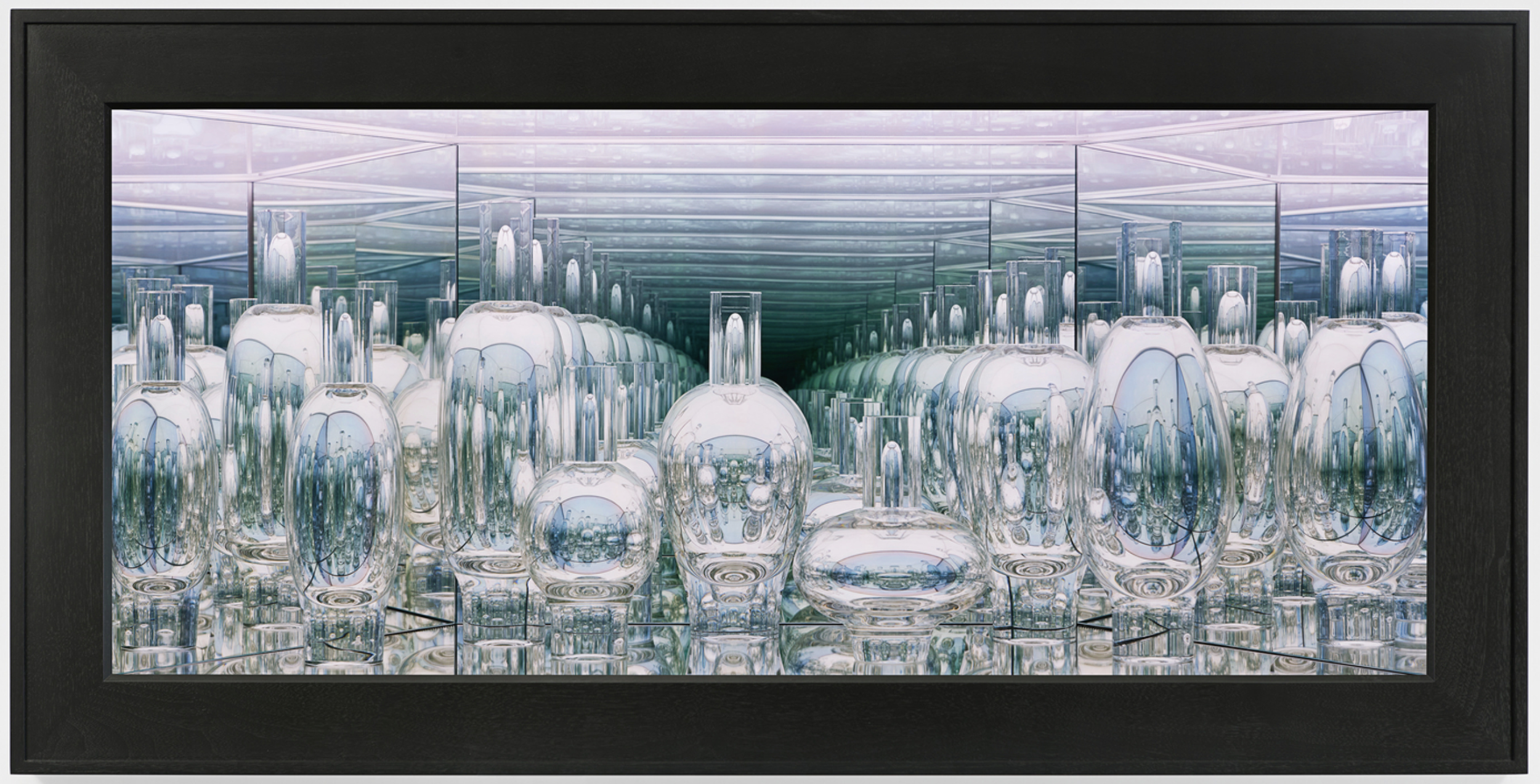

Read MoreIt takes me a few minutes to understand why I feel so uneasy in front of Josiah McElheny’s “From the Library of Atmospheres II.” a sculptural glass assemblage at James Cohan’s 48 Walker Street gallery. It is, I finally realize, because though I am fully aware that I am peering into a world of glass and mirrors, my reflection is missing. Like a child or a puppy encountering an unfamiliar object, I keep stepping closer and further away from the work, tilting my body from side to side, as if convinced that by finding the correct approach I will solve the puzzle presented.

My efforts are in vain. I feel like a vampire. A ghost in the gallery.

McElheny achieves this haunting effect with a simple trick; the clear glass window I am looking through is in fact a two-way mirror like the kind in tv detective show interrogation rooms (perhaps also real ones; I’ve not had the pleasure). Observing this work, I’m intensely hyperaware of my presence in relationship to the art. I am removed, on the outside looking into an enclosed world where McElheny’s carefully arranged hand-blown bottles exist in their own mirrored isolation. It is also an interrogation room of sorts; the bottles in ongoing conversation and observation with themselves—a self-interrogation, an, as McElheny describes, “infinite narcissism.”

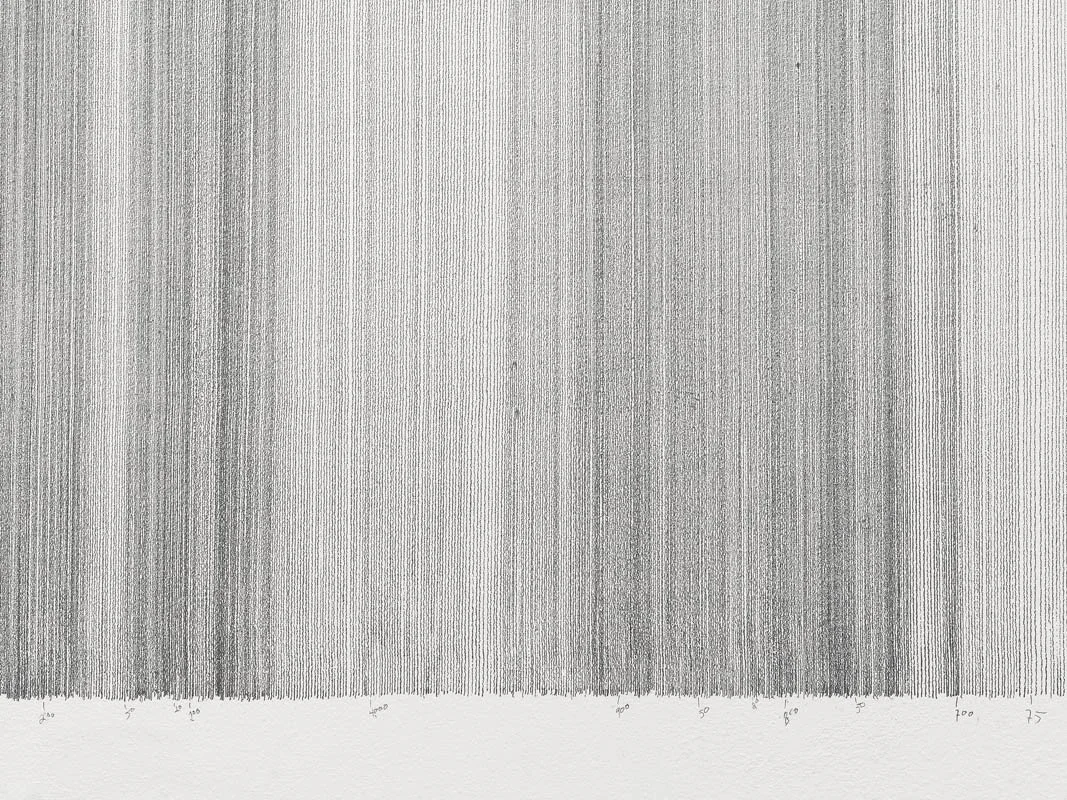

Read MoreThe distance from San Juan, Puerto Rico to El Barrio in Harlem is approximately 1,610 miles. By plane, it’s four hours—give or take tail winds—plus traffic and the TSA line. By boat, a few days with stops along the way. FaceTime and phone calls seemingly shrink the space from here to there, but the expanse swiftly returns. Since 2003, the Puerto Rican-born artist Tony Cruz Pabón has meditated on the true immensity of distance, using graphite pencil to attempt to draw a line the physical length from his San Juan hometown to places elsewhere on the map.

It is an exercise rooted in failure. Each iteration of Cruz Pabón’s Distance Drawings is newly created in situ at galleries and museums around the world, from Berlin to Brazil to his latest attempt in El Museo del Barrio here in New York City. The works are always limited by the time and space allotted by the galleries, as well as the physical demands of the body. Working only with a pencil and a piece of wood that serves as both straightedge and measuring device, Cruz Pabón painstakingly charts these abstract representations of distance and time directly onto the gallery wall, drawing line after line while the other works of the exhibition are mounted around him.

The version in El Museo covers the length of one wall in tightly spaced horizontal lines that wiggle slightly over the natural bumps and texture of the gallery-white paint beneath. The spacing between the thin lines is imperfect, creating patterns of light and dark, a gradient representation of the dark and light aspects of journey, travel, and diasporic experience. Like the final squished-together letters on top of an amateur birthday cake, the lines start to lean and tilt in increasingly more dramatic increments until they reach the opposite wall and cause the artist to run out of space, tiny early errors magnified. Though he worked consistently from morning to night for nearly three weeks prior to the show opening, he was ultimately only able to complete about 5.2 miles of lines, a distance that amounts to a mere .32% of the journey.

Read More