I spent a lot of time thinking about what kind of art one would want in a space like a hospital; a place where events wonderful and terrible, mundane and terrifying, joyful and heartbreaking are constantly and simultaneously occurring. Unlike the usual bland wall décor typically found at corporate hotels or standard doctor’s offices, the pieces at NYU-Langone don’t exist just to fill wall space. This is art that feels engaging, varied, and thoughtfully selected. It is work that seems to have things to say, though never so much that it pulls focus or takes over the room. The art is there to support the mission; it is not the purpose itself.

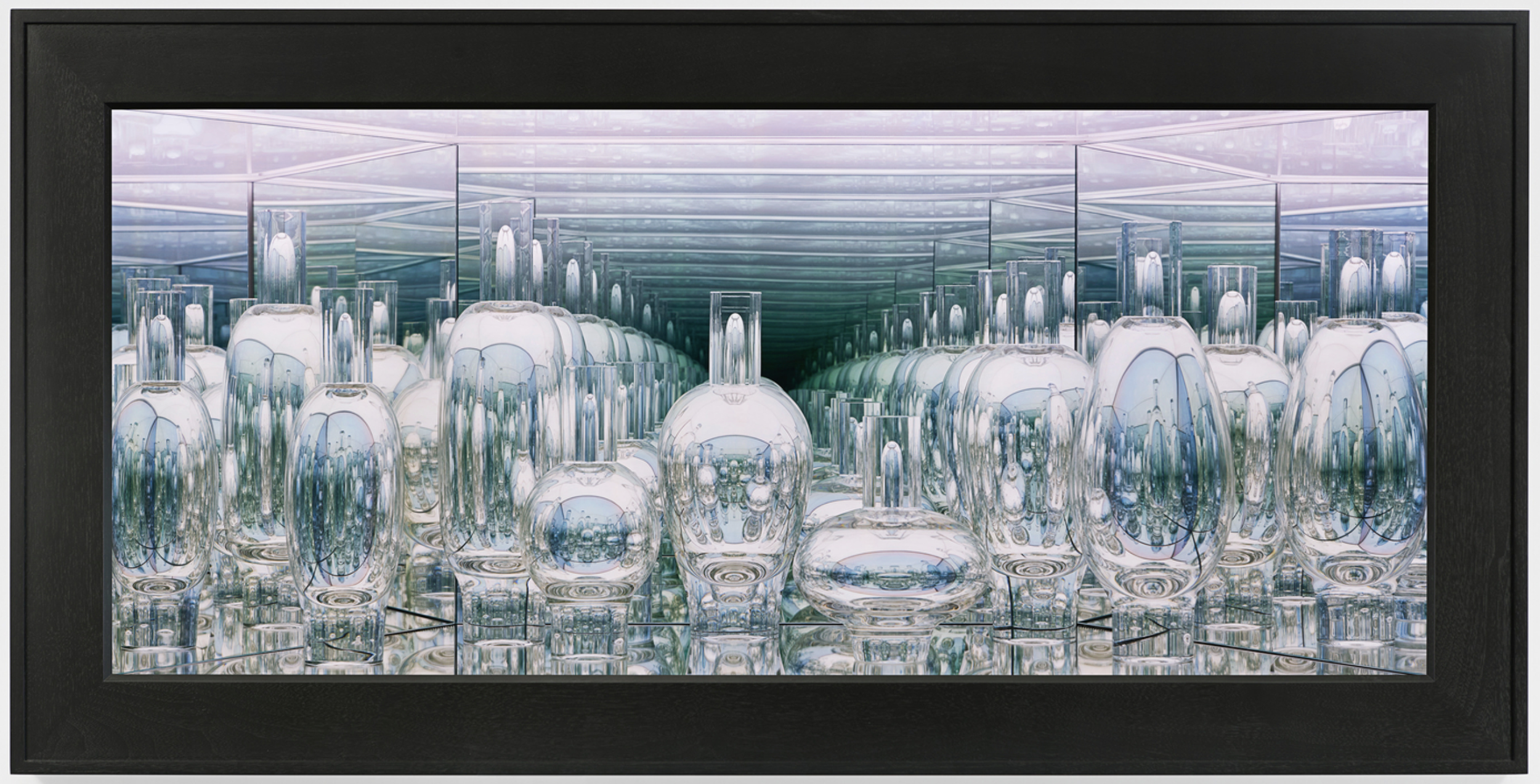

Unlike the deliberately bold Spot!, the majority of the works I saw in the adult spaces of the hospital avoided the figurative and leaned toward total abstraction. Like the iridescent twisting waves of The Moon’s Eyelid by Alyson Shotz (2018), the bright screen-printed color stripes of Royal Curtain by Gene Davis (1980), or the Turkish onyx twists of the sculpture In Pursuit by Leon Axelrod. Emotionally, the works are overwhelmingly calming, often encouraging, playing with color, shape, texture, and light in ways that allow for joy without demanding it.

My absolute favorite of the pieces I saw while my husband dozed in his anesthetized stupor is the sunlight-catching Glissando, a 2013 mixed-media installation of clear polycarbonate Lexan squares suspended with thin stainless steel and aluminum wires. By the artists Tim Prentice and David Colbert, the piece stretches and cascades over the sunny lobby connecting the hospital’s Kimmel and Tisch buildings. In many ways, this silent musical performance seems to best capture the spirit of a collection that is ready to come alive and share its stories with anyone interested enough to pay attention, but just as easily recede into silence for those with other, more pressing, concerns.