I try to remember to pack a few black washcloths when I travel for work. I place them next to the hotel sink, ready to be used when I get back from a shoot, sparing the provided pristine towels from smears of jet black mascara and kisses of Dior 999. When I forget, the association is immediate. A face imprinted on cloth. An unintentional self-portrait—not of my own face, but of the one I wear to do my work…

Read MoreThe marquee image for the 2020 MoMA PS1 exhibition “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration” curated by Dr. Nicole Fleetwood, is from a mixed-media portrait titled “Locked in a Dark Calm,” by the artist Tameca Cole. Though in digital reproduction it appears substantial, it is a relatively small piece—only about the size of a standard sheet of printer paper. In the work, the fragmented figure of a Black woman looks out from the center of a swirling charcoal and graphite cloud which extends to the edges of the page. The head and torso of the woman appear in a gray shadow, mostly obscured by a charcoal maelstrom that swirls in haphazard loops around and through the central figure, mummifying the silhouette. Collaged over the whorls in the center of the page are the parts of a face cut from magazines: a pair of full unpainted lips, a nose, and a pair of dark brown eyes—one stoically gazing off-center into the distance. The other, significantly larger, and side-eyeing directly out from the canvas as if keeping a skeptical, watchful eye on the viewer…

Read MoreDear Lars,

I remember you telling me Cerpa is Puerto Rican, and I was particularly looking forward to spending time with his work here in this dearth of Latino-ness. Even when there is nothing specifically “Latin” or “Puerto Rican” in the work, I always have this underlying sense that somewhere along the line there must be a dash of commonality. Even something as tiny as a type of food, a phrase, a tradition, a habit. Something in the recipe of this person that mirrors the recipe of my person that eventually sneaks into the work itself like a form of common terroir. Not that this equals knowing.

One of our filming days here is set aside as a “Promo Day,” where we do things like photoshoots for the show poster and ads, video interviews with the publicity team, etc. (This may feel like a digression, but I promise it’s not.) One question I’m asked over and over is “How does food build bridges between cultures?” I hate this question because it oversimplifies and makes assumptions…

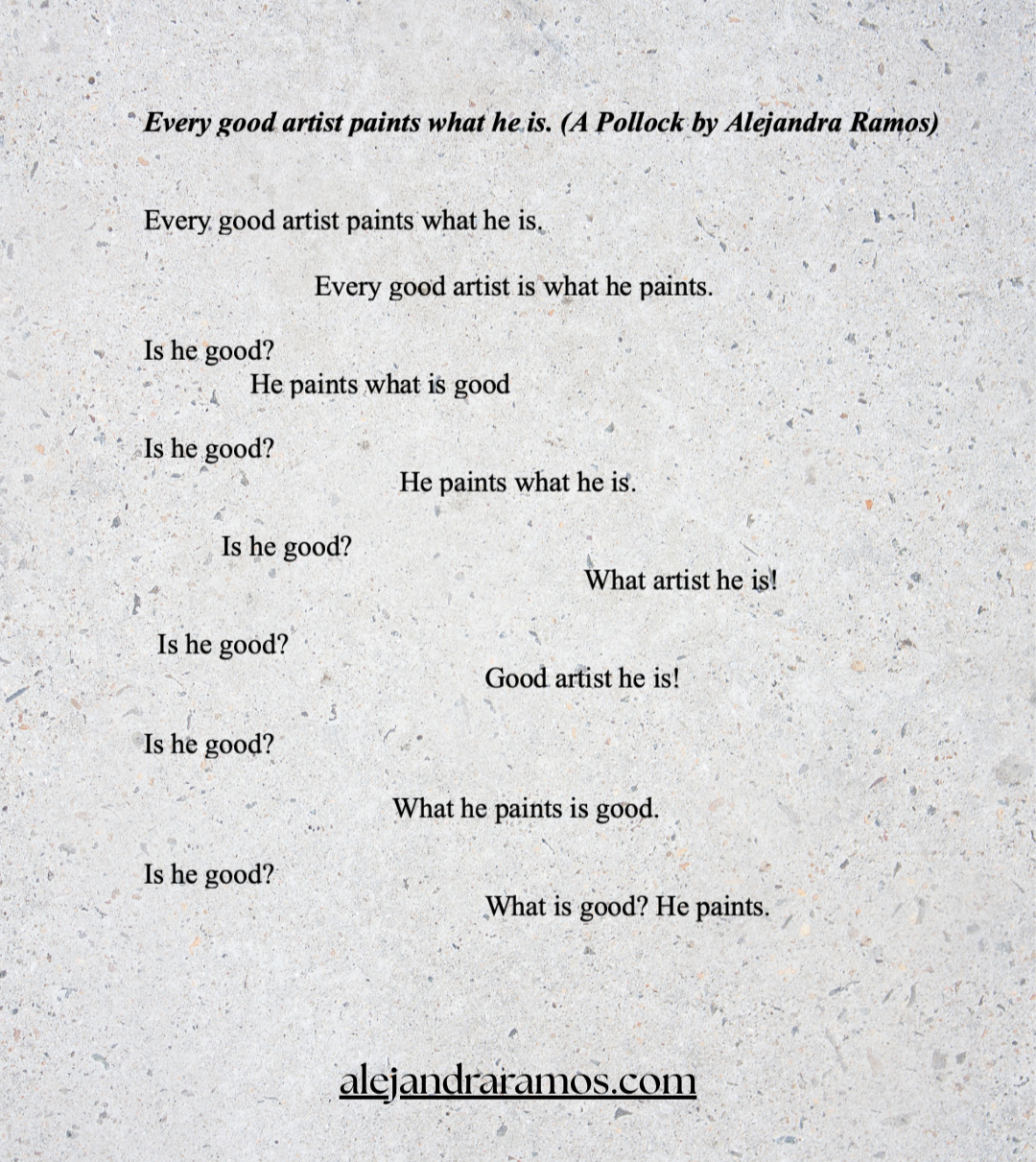

Read MoreCreated by the poet, curator, and art critic, John Yau (b. 1950), a “Pollock” is a playful and inventive poetic form that pays homage to the work of the abstract expressionist painter Jackson Pollock (1912 - 1956). The “rules” are simple and reminiscent of Pollock’s own methods. Yau first used the form in a poem called “830 Fireplace Road: Variations on a sentence by Jackson Pollock.”

A Pollock is a 14-line poem that must begin with a line or quotation said by the artist. This initial line serves as your poetic painter’s palette, so to speak, from which you will then create the subsequent thirteen lines…

Read MoreThe sunlight streaming through the sepia-red corton steel bars of Edra Soto’s GRAFT (2024) installation at Doris C. Freedman Plaza in Central Park decorates the asphalt terrace with geometric patterns of light and shade that bring forth a flickering rush of memories.

Morning sun rising through the window grates of my cousin’s teenage bedroom while someone brews coffee down the hall. The coolness of the damp golden sand shielded by palm frond silhouettes. Fading light sinking down textured terracotta walls in my aunt’s Ocean Park courtyard.

Though the work itself also feels familiar, reminiscent of so many homes and places in my family’s native Puerto Rico, there is something specifically about the way Soto’s art interacts with the space it inhabits that strikes a particularly resonant chord.

Read MorePeering through the frosted glass door, the gallery looks closed. It’s a few minutes past five and only a handful of people remain on the street, ducking into doors one or two at a time. Most have wandered off to meet friends for happy hour or settle in for an early dinner. Inside, the light feels dimmer than it should be, but I assume it’s intentional and say nothing.

Moments later, a mother hesitates at the door before walking in with her young son. “We thought you were closed!”

The gallery sitter apologizes. I catch only bits of it: Something about how the lights keep flickering. Less annoying to keep them off. It’s better when it’s sunny, but the clouds are thick today.

“We’re just scraping by without light” (I write this part down.)

The boy races to the opposite side of the gallery. The mom laughs like a bell and follows him. He’s free in his movements yet knows enough not to touch.

The brightest part of the room is in the center under a paneled glass skylight that sits directly above a polyurethane copy of…

Read MoreIn her lecture “On Beginnings,” collected in the book Madness, Rack, and Honey, the poet Mary Ruefle considers Gaston Bachelard’s idea that “we begin in admiration and end by organizing our disappointment,” which she simplifies even further into “origins (beginnings) have consequences (endings).” Pulled and paraphrased from Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, where it originally referred to the practice of poetry and the ways we deal with the intrinsic inadequacies of language, it is a concept that can also be applied to an act even more mystical and bewildering: that of falling in love.

As Ruefle elaborates, “the moment of admiration is the experience of something unfiltered, vital and fresh” not unlike the sense of potential, amazement, and naivete with which one might enter a new romance. As the initial illusions fade and the realities make themselves known, the clarity afforded by disappointment becomes an opportunity to take agency and make decisions in marked contrast with the uncontrolled fall at the onset. Or as Ruefle puts it, a moment of “dignification” where the writer—or for our purposes, the lover—can take back control of the story.

For writer and director Nora Ephron, dignifying the consequences of her origins meant using it as fodder for her literary work. From the Esquire magazine essays that pulled from her daily life to the dynamic romantic comedy heroines she wrote to deliver her personal philosophies on screen like Meg Ryan-shaped ventriloquist puppets, Ephron was an unapologetic miner of her own lived experience; a self-described “cannibal” who took her screenwriter mother’s adage to heart that “everything is copy.”

Read MoreIt begins with a canvas covered from end to end, a single color.

Perhaps orange? Perhaps blue.

(Echoes of a long-ago lesson about restoration: the solid and color-blocked works are more difficult to restore. The simplicity puts the emphasis on the brushstrokes and texture, the errors more noticeable, the damage, the aging, the chips, the fades.)

The canvas is of an average size, slightly larger than a large book, something that can be carried.

(That is the main rule of this.)

We’re calling it reckless and it is a co-creation with accident.

Read More