The distance from San Juan, Puerto Rico to El Barrio in Harlem is approximately 1,610 miles. By plane, it’s four hours—give or take tail winds—plus traffic and the TSA line. By boat, a few days with stops along the way. FaceTime and phone calls seemingly shrink the space from here to there, but the expanse swiftly returns. Since 2003, the Puerto Rican-born artist Tony Cruz Pabón has meditated on the true immensity of distance, using graphite pencil to attempt to draw a line the physical length from his San Juan hometown to places elsewhere on the map.

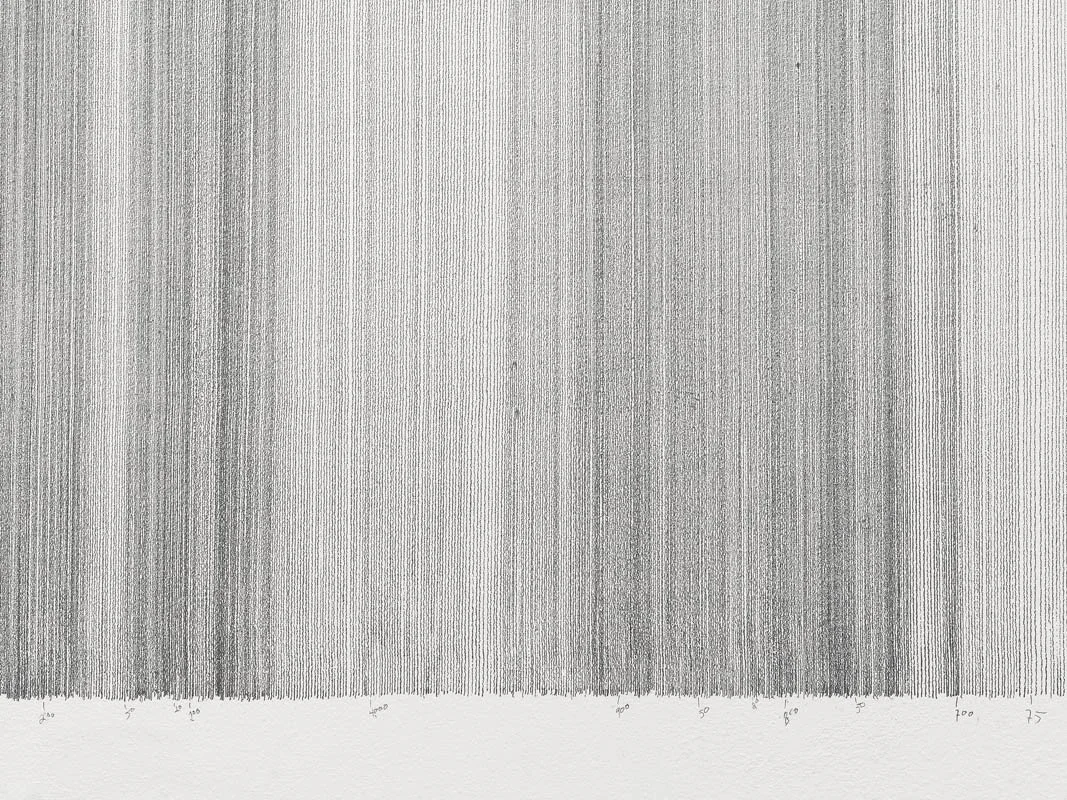

Distance Drawing, Tony Cruz Pabón (b. 1977). Attempt to draw the distance between San Juan and New York (aprox. 1,610 miles). Realized only 0.32 percent (5.1523 miles). Graphite on wall.

It is an exercise rooted in failure. Each iteration of Cruz Pabón’s Distance Drawings is newly created in situ at galleries and museums around the world, from Berlin to Brazil to his latest attempt in El Museo del Barrio here in New York City. The works are always limited by the time and space allotted by the galleries, as well as the physical demands of the body. Working only with a pencil and a piece of wood that serves as both straightedge and measuring device, Cruz Pabón painstakingly charts these abstract representations of distance and time directly onto the gallery wall, drawing line after line while the other works of the exhibition are mounted around him.

The version in El Museo covers the length of one wall in tightly spaced horizontal lines that wiggle slightly over the natural bumps and texture of the gallery-white paint beneath. The spacing between the thin lines is imperfect, creating patterns of light and dark, a gradient representation of the dark and light aspects of journey, travel, and diasporic experience. Like the final squished-together letters on top of an amateur birthday cake, the lines start to lean and tilt in increasingly more dramatic increments until they reach the opposite wall and cause the artist to run out of space, tiny early errors magnified. Though he worked consistently from morning to night for nearly three weeks prior to the show opening, he was ultimately only able to complete about 5.2 miles of lines, a distance that amounts to a mere .32% of the journey.

These numbers are included in the wall description of the art, the lapse very much a part of the piece where the failure is by design, showing the inestimable elements of feeling far from one’s home. Though there would be ways to complete the task, perhaps using technology, a team of assistants, or a more long-term exhibition space, Cruz Pabón has deliberately chosen to work alone and with physical limitations as a reflection of life on an island like Puerto Rico where geography, climate, and politics regularly jut against the needs and desires of its inhabitants. There is also intentionality in the choice of the ephemerality of the work. At the end of each exhibition, the pieces are erased. Another reflection of life on an island where ocean waves wipe away footprints and sandcastles. Where salt air erodes. Where storms decimate. Where culture, customs, and language are being slowly effaced.

In thinking about my own curation, I was drawn to Cruz Pabón’s exploration of distance as a Puerto Rican who, like so many others in the diaspora, was born and raised away from the place that felt like home. How do you chart distances that exist outside of tangible space? How do you represent that which can’t be represented? Cruz Pabón’s acceptance of the inevitable failure of this task also feels relevant to the task of curation itself where every inclusion is a hundred exclusions, and our choices are limited by physical space, time, our access, and the individual experience we bring into our selections. (Particularly if we return to the sentiment of curation as remedy or restoration…of filling in gaps.) The work serves as an acknowledgment of the insurmountability of the task. That the work is in the attempt.