A preface:

I’ve been going back to the reading journal I kept last Fall while filming Season 4 of my PBS television show. We filmed the episodes in Nashville, TN, and as I was enrolled as a full-time student at Columbia in NYC, that semester, I negotiated alternative assignments with my professors to make up for the handful of absences. In lieu of in-person discussion, I submitted a journal of responses to the assigned readings. Am posting a few here as a record and a reminder:

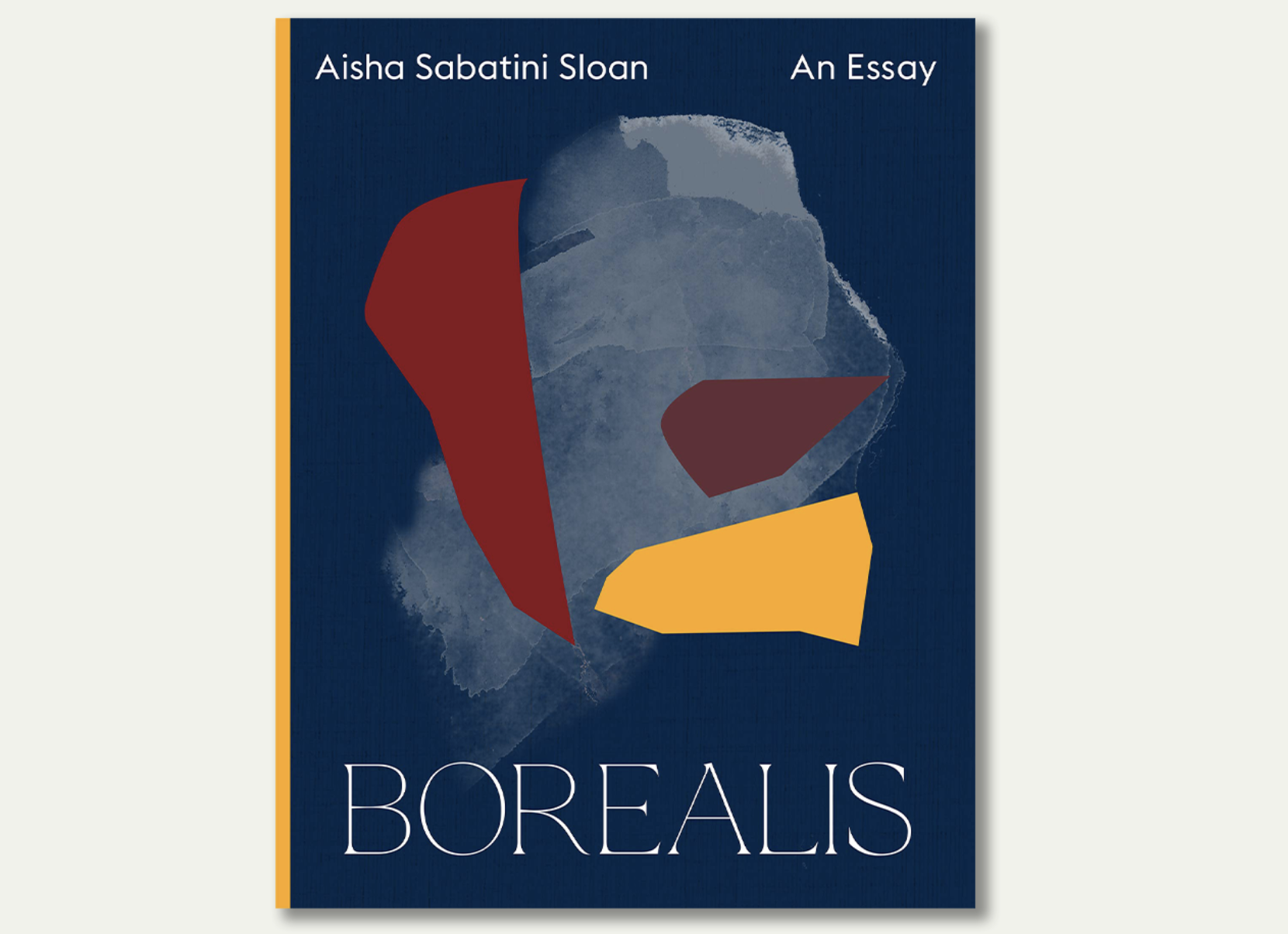

Aisha Sabatini Sloan | Borealis | Coffee House Press | 2021 | 144 Pages

October 2024

Nashville, TN

In Response to Borealis by Aisha Sabatini Sloan

Dear Lars:

It occurs to me that we never discussed specific parameters for this reading journal, but I feel drawn to a letter format, partially inspired by the letter-style foreword to Aisha Sabatini Sloan’s Borealis.

That was, in fact, the first thing that struck me about the work. It’s something I can’t recall ever having seen before although it makes perfect sense. I suddenly feel like every foreword is in some way, a letter, (signed, dated, in conversation with the work, etc.) though I suppose they usually addresses the reader rather than the author. I like this new-to-me approach and feel like it’s something I may want to use in the future when writing introductions or blurbs—I’m often stuck with what/how to write and suspect the idea of framing it in my mind as a letter to the author could prove helpful.

One of the other things I noticed as I started to move through the work was a feeling that I was reading the structural mirror image of Jenny Bouley’s The Body: An Essay. There we had footnotes with no essay; here we have a highly referential essay with absolutely no explanatory footnotes.

Reading Borealis, I felt equally unmoored, with a nagging desire to stop and look things up to fill in the gaps of my knowledge. I noted that in the moments when I either completely understood the reference or knew absolutely nothing about it, I was more likely able to continue reading without interruption. In the moments where I only had partial knowledge or a more vague understanding, I found it impossible to keep reading without stopping to fill in the gaps. It was the same sensation as when a word is “on the tip of my tongue.” A piece of knowledge existing so slightly out of reach that I’m consumed by it. It wasn’t until I reached the part about the murder mystery novel, which I recognized as Blood from a Stone by Donna Leon because I’m obsessed with detective stories, that my instinct to solve the puzzles made a hilarious sort of sense to me.

Just as with the previous works we’ve read and discussed in seminar, this format made me think about what we give and what we withhold when we write, both in terms of actual purposeful literary structure like plot and character development, but also the decisions we make about how we want to interact with our reader. Do we offer them a hand? Do we expect them to meet us? How much discomfort or disorientation is too much? Where is the line between challenging the reader and obscuring the message? And, of course, who is (or isn’t) granted the ability to push these boundaries.

Andrés and I have had conversations about this in past classes regarding the ways we use Spanish language in our work, and a lot of it often comes down to wanting to push back against the usual expectations of the dominant class as well as a recognition that there are things that will never translate no matter how hard we’d like them to, as well as things we would prefer to keep for ourselves. (I don’t need to tell you that this obviously expands far beyond questions of mere language.)

Reading about Sloan’s time in Alaska while away from my own home made the text feel all the more present. The magnified physicality of existing as a body in a new, temporary space mirrors my own experience here in Tennessee, a place I appreciate aesthetically, but find culturally alienating. I feel my nervous system in a heightened state of alert here in new and different ways than what I feel at home. In some cases I found myself exclaiming out loud about Sloan’s anecdotes which felt like frame-by-frame retellings of things I’ve encountered here: signs on restaurant doors saying guns are not permitted inside (which instantly send me into a panic wondering how many folks are walking around outside with them on their person) and the pointed interactions with locals who (as Sloan noted) go out of their way to show me that while the state may be “pretty red” we’re on “the same side of things.”

I love the times where Sloan notes that she feels she is the “most interesting” person (on the beach, in the room, etc.). In one moment, she talks of writing “a list of black figures in Alaska,” and goes on to include a few examples—a girl walking down the road, a man in a beige hoodie, a Tessa Thompson-style girl who holds a door open for her. She also notes the moments she spots other lesbians; the longing for recognition (“someone with whom to discuss Jenny from The L Word”). I realize I’ve been unconsciously doing the same looking for other Latinxs here. So far I’ve only met three: the Peruvian chef who runs the catering truck that feeds our crew; a PA who tells me her mother is from Quito when overhearing me tell a story, and one of the contestants on my show. During a break, I tell my colleagues about this and playfully ask one of them: “When you walk into a room, do you count how many other white men there are?” “I can’t count that high,” he joked back.

Returning to the format of the book, which I find so fascinating. I admit it wasn’t until reading Sloan’s note in the acknowledgments about starting with the prompt to reenact Georges Perec’s work that I understood the project, and if I’d had time, would have gone back to reread it keeping this in mind. (Unfortunately, I absolutely do not have any time to spare this month, but I plan to in the future.) But I’ve been thinking about the way that recording observations reveals patterns, both in our own behavior and the world around us. Reading them as a book I start to feel sense of boredom about the repetition and continuous starts and stops. This makes me think about the nature of narrative and what drives a story. What pulls a reader along? In many ways, the experience feels like an exercise that shows why editing, deletions, and omissions are necessary.